THE CHALKBOARD GUIDES: THEIR PURPOSE, RATIONALE AND MAKE-UP

The Chalkboard Guides are innovative teacher guides that are more adoptable, more supportive and more cost-effective. Harnessing the power of structured pedagogy, they provide teachers with board models, sharpening subject knowledge and targeting scripting to where precision makes the most difference. In this way, teachers, from novice to expert, can use them to improve learning outcomes for their students.

Once we have a proof of concept for the pedagogy that drives the Chalkboard Guides, we want to use its component parts for short animated demos, audio clips and worksheets that teachers can assemble into blended learning solutions for their students and use for their own professional development, all at the click of a button.

PURPOSE AND RATIONALE

We are aiming to teach all our students to read by 3rd grade. To do this, we need to have a higher baseline standard of teaching across our schools. Our strongest teachers have mastered the art of breaking down new ideas for the children they teach and hold their students spellbound, creating calm, joyous learning environments. Whether naturally gifted or reflective practitioners, these teachers have long excelled in our schools, even before Justice Rising made concerted efforts for programmatic change. Weaker teaching in our schools looks like insecure subject knowledge, slow pace, and children enthusiastically participating in rote learning but not really having to think very deeply. Eyes glaze over as children find they cannot follow the lesson; the teacher goes through the motions of teaching; children aren’t learning.

When we introduced ‘I do, We do, You do’ as a modeling technique in 2018, we integrated it into the existing teaching model and every teacher practiced with their peers. Those who tried it out with their classes saw results really quickly, and they adopted the technique as their own. Some teachers didn’t try applying it in their classrooms, the step from teacher training conference to their own personal classroom proving too big a jump.

We thought about coaching - honestly, we are still iterating on coaching, trying different approaches that can work in our context. But we wanted to find a way to reach every teacher, in their classrooms, so that every child could spend all their time in lessons learning.

In considering how to improve learning outcomes, we noted elements of education that transcend context (though they vary vastly in quality), so we could look at the evidence for where the intervention should focus.

We have seen interventions around class size, textbooks, workbooks and endless interventions that focus on the teacher: rightly so. Teachers, as we all know, can make or break learning; their mood can swing a lesson this way and that; their strength determines learning outcomes more than any other factor.

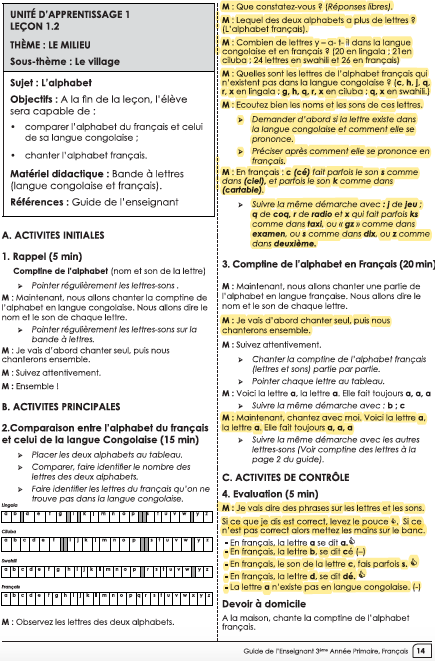

But what other enduring factors can support teachers? Textbooks can be brilliant, but are expensive. Teacher guides are extremely promising but in their current form still leave a margin for error in their interpretation and vary in quality. For example, this guide from the DRC tells the teacher to read a text to the class.

One teacher may share the text from the board then read it out, another may read it straight from the guide with only a picture for students, another may put a copy of it on each desk.

In the first instance, the class may or may not be able to follow along, depending on the size of the text and whether the teacher points to the words as they read. In the second, the class misses out on having the act of reading explicitly modeled to them. The third relies on more resources, but means the class could follow along as the teacher reads.

Lesson guides support changes in teacher behaviour, but whereas scripts dictate exactly what teachers say, this kind of precise support does not tend to extend to what students have in front of them during the lesson, which really matters. Show and tell is far more powerful than telling alone. Although lesson scripts are oft-accompanied by workbooks containing such stimuli, this is of course, at further cost both in development and production, and not always consistently produced.

Chalkboard Guides deliver what workbooks and lesson guides deliver at lower cost, empowering teachers to present powerful stimuli on the board: precise subject knowledge, clearly set out, following the I do, We do, You do model, thus incorporating the strengths of structured pedagogy and bringing it alive at the board. They embrace the power of the board as a learning tool; empower teachers to maximise its impact; engage students to think more deeply and learn more, every lesson.

Let’s look in detail at key aspects below.

THE BOARD AS A TOOL

The board is an immensely powerful tool for teaching because it allows the teacher to show students concepts, knowledge and skills in a way that is not possible with only verbal means. Teachers can emphasise, explain, question and demonstrate with a board. They can also be used to set independent work for students and serve as a focal point for students’ attention. The board is optimal for demonstration because of the ease with which teachers can orient students (by pointing) around a single example, making it easier to follow the teacher's demonstration. Because show and tell is really a very effective way of teaching, the board shines as an outstanding teaching tool: it is to teachers what a scalpel is to surgeons. And it is also economical, easily repairable and replaceable: this ubiquitous teaching tool is used in millions of classrooms worldwide, everyday, but to varying degrees of success. By supporting teachers to improve how they use the board, we believe this will quickly translate into better learning outcomes.

SCRIPTING

They script only the worked example or "I do" and "We do" part of the lesson, or particular areas where precise subject knowledge is paramount. Based on research, the World Bank (consultation document) and RTI recommend lighter scripting and scripting that lightens up as you go, respectively, but I would venture that some elements need to be scripted over others. Exactly how a teacher gives an instruction to open to page 11 is far less important than the steps a teacher verbalises whilst demonstrating how to answer a comprehension question. I highlight below the parts of an example script that are more powerful than the rest: key questions, explanation, and I do, We do, You do steps.

These parts are more important because they contain exactly how the new learning will be presented by breaking it down into small steps. The teacher will model how to approach a question, gradually hand it over to students to follow that same model, then have a go themselves. It makes a higher success rate more likely, which in turn increases motivation. Of course, scripting instructions will impact some kind of activity in the room, but activity and engagement don’t necessarily lead to learning. A teacher can tell their students to sing a song in a variety of ways. How they teach the content of the song is more important.

Key takeaway: script key questions, explanations and I do, We do, You do steps; don’t script instructions.

ENSURING PRECISION WITH SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

By giving teachers a script for what is to go on the board, Chalkboard Guides ensure errors/misconceptions are not being taught and reinforced. Where other sources of knowledge are scarce, children may be less likely to pick up on teacher errors. The scripting of the “I do”/teacher demonstration, further supports teachers to break down the content into small, manageable chunks - a key principle of instruction.

LAYOUT AND ORDER

The Chalkboard Guides take scripting even further, setting not only what teachers should write on the board, but how it should be presented on the board. This matters because the way knowledge is organized (visually) significantly impacts our ability to learn it.

I would venture at this point that board guides will increase fidelity to the guide because they are inherently more intuitive and useful for teachers to use.

I DO, WE DO, YOU DO

There are parts of the lesson that lend themselves well to I do, we do, you do, and parts that don’t. I do, we do, you do is a really useful tool, but just as there’s no point using a hammer to cut up wood, this gradual release strategy won’t work everywhere. I do, we do, you do is a modeling tool, used like so:

Teacher Guide example from Liberia

I do: the teacher demonstrates exactly what they want the students to do, highlighting the new knowledge (adding -ed)

We do: the teacher asks students to join them in adding -ed to bump.

You do: the teacher asks students to have a go themselves.

Here are some examples of where it is being used, but not for its core purpose of modeling:

Teacher Guide example from Malawi

In this example, this part of the lesson aims to teach children new vocabulary. To use I do, we do, you do for this does not work. What if nobody in the class knows the meaning of ‘show’? What if the ones who think they know have a slightly skewed understanding of its meaning? (Also, in this example, the teacher does not model giving the meaning of the word ‘lonely’ in the I do, which also undermines I do, we do, you do.) So what should have happened here, instead? With the help of a dictionary, the teacher could:

Model reading the word aloud

Read it aloud within the context of the text wherein the class has come across it

Find it in the dictionary

Read the definition aloud and

Use that word in another context for consolidation

These are steps that children could follow (if they have dictionaries to use) to give meanings of words they don’t know.

(For settings where dictionaries are not available, it would be better to give teachers the meanings to share with students, then use ‘I do, we do, you do’ for a consolidation activity, such as using the newly learned word in a new context.)

Teacher Guide example from Malawi

In this example, it’s really good that teachers are given prompts of what to do during the you do, but again, ‘I do, we do, you do’ is a modeling tool, and so:

the ‘I do’ should demonstrate Exercise A;

the ‘we do’ should be the teacher leading Exercise B with input from learners;

the ‘you do’ should have learners completing Exercises C (and the teacher checking their understanding) then continuing on with exercises D-H independently, whilst the teacher targets their help to struggling learners.

Without the two demonstrations of Exercise A and B, it is far more likely that the teacher will have more struggling learners than with them.

This particular teacher guide frequently used ‘I do, we do, you do’ three times per lesson, indicating that the writers are using the tool to perhaps boost interactive, engaging teaching. Whilst the tool is inherently interactive by nature, I would suggest that its core purpose is modeling. (Cue whoever invented it gets in touch and tells me I’m wrong…)

Key takeaway: Use ‘I do, we do, you do’ to show children how to do the thing that they are going to practice and consolidate - the thing they will learn in that lesson.

ADOPTABILITY

There's little point developing a really strong tool if it doesn't handle well. Teacher guides need to feel helpful to teachers, be easy to navigate and return a near-instantaneous positive impact in order for any changes to stick. Chalkboard Guides support the use of an indispensable everyday teaching tool, come in a one page per lesson booklet, and after one demonstration should be highly intuitive for teachers to use. By using an iterative design process, we hope to iron out barriers to adoptability early on, in field tests, as well as gaining precious feedback on design and content.

PHASE 2: BLENDED LEARNING SOLUTIONS FOR TEACHERS AND CHILDREN ALIKE

Schooling ≠ learning (and this is the same for remote learning). Teachers are best placed to assemble remote learning for children, but classroom simulation ≠ the best remote learning experience for children.

The biggest differential factor with remote learning is the teacher's absence - it means:

No re-explanation - redress with pause and replay; explain from different angles and contexts

No dynamic social interaction (maintains engagement because it's fun) - redress with playful characters and other fun factors

No encouragement to keep going - redress with animated praise

No supervision - provide extra scaffolding throughout clips and embed self-assessment facility (will also aid metacognition)

No immediate feedback - give the answers somehow to give feedback

No checking for understanding - embedded self-assessment will support children to check their own understanding, and return to the explanation clip if they missed it.

Once we have board lessons that are working in the classroom, the next step is to create animations of the 'I do'. No longer than 5 minutes long, and using fun animated characters throughout, these short clips would provide continuity of learning scaffolds between school and home, with the animated characters modeling the exercises that children will then complete in a complimentary workbook that children bring back to school or teachers collect to give feedback.

Developed with support from Oxford Measured